Travel offers unique perspectives into how people in other parts of the world live, and of great interest to us, dine. But It wasn’t until Lukka and I were wandering around Buenos Aires in December that I began to take in just how profoundly, no matter where you live, food patterns have changed. Buenos Aires is a city with an affordable and vibrant dining community but wherever we traveled, in every neighborhood and down every street, motorcycles and bicycles were flying around with their sagging food delivery bags hanging off the rear.

To be clear, on the late nights out we walked home we passed restaurants still full to bursting, inside and out. We dined with delight in historic food halls where hundreds of individual purveyors hung their entire menu -all their proteins and vegetables - over their food stations seperated by only a few feet from dining counters and huge picnic tables that ran the length of the stadium sized building. This wasn’t fast food - it was thoughtful and delicious. We dined at white table cloth restaurants that spilled out onto the streets with diners of all ages, many couples with children, many animated conversations often with diners next to them they did not know. There was an elegant insouciance to dining in BA we fell in love with, but man, all those PedidosYa, Rappi and Door Dash motorcycles- and quite a few wonky bicycles - they were ubiquitous.

I get it. No matter where you live in this age of online consumerism all it takes is one phone call and a brief interaction at the door and food is there in front of you to be consumed in the comfort of your own home, no matter how humble or grand. You don’t have to get dressed. You don’t have to deal with the cacophony of outlier conversations around you, don’t have to calculate that extra drink, or even how much to drink, or what to tip. But here’s the thing: unless you shopped and cooked for that meal or ventured out to a restaurant to share it over a table in conversation, except for spending yet more time with a technology whose only goal is to hold your attention in order to monetize your behavior, what did you really nourish in letting an app dictate your appetite?

In conversation with the NYT’s David Marchese the writer George Saunders recently spoke about ‘the rate at which we’re being encouraged to forgo human to human activity.’ With so much to try and make sense of in the world, he made the point (he happily credited to Chekov) that our most important job as humans right now is not to have the answers (or rely on AI for them) but learn how to formulate our questions, better. “It all begins with a key recognition that true attention cannot be measure by a machine. The fullness of our authentic human attention, shared with others, is the power with which we make the world. It’s worth fighting for.”

Food carries an indelible footprint of a journey that tells the story of land and nature and culture. We risk losing an essential part of our humanity when, for lack of attention, we cut the threads of knowing where our food comes from, whose hands and talents caused it to appear before us to be consumed. Of all the social interactions we are compelled to do - working, shopping, attending to our health and to the needs of our families - dining out is a choice. It is imperfect, to be sure, but as both an art form and a service industry it is a true reflection of both the strengths and frailties of human nature we all share. When groups of strangers gather to dine they transmute something indelible across a room, a connection to the larger community and we break those connections at our peril. The loneliness and isolation which is a result of our increasing dependence on algo-rhythmically driven relationships has only one antidote - human to human interaction for which, lets face it, there is no substitute.

So much is in play at this moment in history as we strive to find ways to live meaningful lives. But whether I’m looking over our dining rooms on Center Street or slipping into an anticipated meal at a restaurant somewhere in the world- fine dining, bistro or gastropub - I am hoping - as the original definition of the word restaurant was intended, to be restored. Give me an interesting room full of animated hungry strangers, throw in one or two people I like or want to get to know better, and I’m halfway there. Alongside a sustainable vision of dining, and a caring staff, in that moment life affords you an opportunity that is increasingly precious … to look around you and think yes, I’m a part of all this, I belong here.

Le Caprice was the restaurant where the Guv and I had our first date, the restaurant Nick Foulkes, my editor at the Evening Standard once took me for lunch and Princess Di, behind the pillar at table 8 gave into a laughing fit so infectious everyone around her started laughing as well. It’s enjoying its third life as The Arlington under the original owner Richard Caring, perfectly executing the original menu of classic dishes the beloved food critic AA Gill - who wrote Le Caprice’s cookbook- described as exemplifying “practiced elan and panache.” (to wit: “energy, style, enthusiasm, a confident way of doing things that inspires admiration”). The enduring success of Le Caprice all those years ago continues today judging from our experience this January in a packed room which felt uncannily similar to evenings we enjoyed three decades ago. It’s is worth considering why, given the state of a restaurant industry all indications point to being in serious decline.

Caprice was built to let the diner unwind, it was all about having a good time, but its success lay in sum of its parts. Good though the menu was (and is) with satisfying classic dishes, it wasn’t just the food; sleek though the room was, and is, all white, silver and reflective, its wasn’t the design (though a clue may lie in the fact the perfectly pressed white linen tables which initially feel too close together enable conversations all around you to all flow as one. It wasn’t the extraordinary floral installations which crept from the bar to the ceiling, or the Richard Avedon B&W portraits lining the walls of the greatest - or at least the most famous actors, playwrights, artists and raconteurs of the 60’s to the 80’s ( most all of them dead now). There was a rather large grand piano just behind the host stand that for two decades was played by an enormous Islander - just loud enough so conversations could get rowdy without anyone caring. The piano is still there. The night we dined there was no one worth craning your neck around to see, yet still, the mood of the room, relaxed and engaging, at our table animated with stories and plans, was a joy, a reminder of why I loved dining here all those years ago.

Then there was this: Caprice has a long, carpeted, extremely narrow staircase leading down to double leaded glass doors that open to the loo’s. It has always been extremely precarious to navigate, especially late at night, a few drinks in, as it was on my recent visit. But then as now, concentrating on getting down safely brought a presence of mind which was briefly sobering. There was a moment over the sinks, looking at myself in the mirror, listening to the muffled laughter, the music, the hum of life from upstairs that triggered a sympathetic déja vu: We don’t always need to live alongside all the pent up feelings we have at the intersection of one’s personal life and history. We should be able to look them in the eye and sometimes let them go with an exalted sigh, because, well, that’s life.

When that release comes in the middle of a social setting with the expectation of a pleasing room filled with color and sound and food which compliments our appetite, it brings with it the experience of belonging, even if to an indiscriminate tribe, belonging no less. It’s a feeling we are in need of, especially now, with so many forces trying to tear us apart. No matter what you are willing or able to spend to dine out, what we absorb from dining out in a room ‘together’ is not something that can be delivered to your door in a plastic bag.

The other memorable meal we had in London over the holidays was lunch at The Devonshire - which we enjoyed with our all time favorite dining companions, Linni and Nick Campbell. We dined in The Grill Room, a bit more posh than the dark and clubby pub on the ground floor, which reportedly has the best Guinness in London. Upstairs is a room of understated elegance dominated by an astonishing wall to wall wood-fired furnace, (see above) the better to produce the embers, ash and smokey flavors Jamie Guy (Hix) and Ashley Palmer-Watts (Fat Duck) have made a signature.

So what makes a great meal out? A tempting menu, great drink, an engaging ambiance, an anticipation of not knowing what flavors you might discover - or re-discover - all play a role in the equation. I’ve had far more super evenings that came with a few imperfect dishes or forgivable lapses in service where the room and the menu vibrated with life; quite a few forgettable ones at temples of gastronomy where playing with your food was frowned upon. A truly great restaurant is one which lets you feel that you, the diner, are an integral part of the equation. And you are crucial. Not just because brick and mortar restaurants cannot succeed without your patronage. You are the music that fills the room with life.

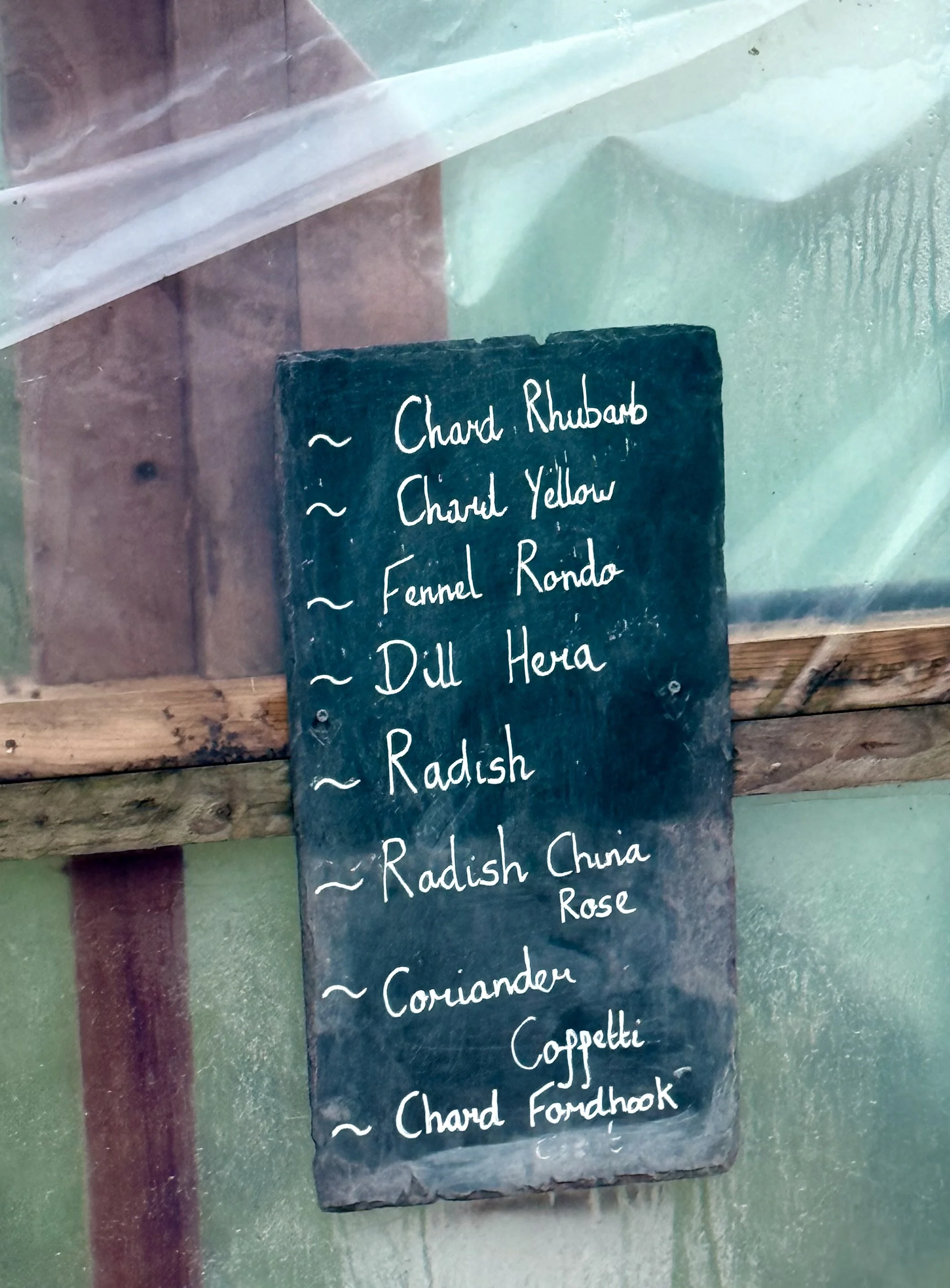

I have written in the past about the food grown on site or sourced within a few miles of The Pig Hotels, and their dedication to a particularly engaging hospitality that honors farm and garden traditions. It still impresses. There are now 9 Pig properties in the UK. a collection, not a chain, as each historical grand house is unique. We love the one in Devon not least because it gives us the opportunity to check in with what Ashley Wheeler and Kate Norman are up to at Trill Farm on Puddleylake Road in nearby Musbury. There are few farmers we admire as much - in addition to supplying The Pig (they grow over a 100 different varieties of leaf and flower) they run regenerative farming courses throughout the year, save seed for their Real Seed Catalogue and Vital Seeds, and are passionate voices in support of the LandWorkers’ Alliance UK and helped set up the UK Seed Sovereignty Programme.

The Wild Rabbit in the village of Dalesford in Gloucestershire sits in the middle of hundreds of farmed and grazed acres that supplies the Village, The Michelin Star Wild Rabbit Restaurant, two taverns, the Erewhon style food hall adjacent to renovated farm house cottages, as well as four Dalesford with restaurants around London. Yes, It’s posh and a bit pricey, worth it for the quality of everything the Bamford Family enterprise does; Carol Bamford’s attention to detail (which stretches to clothing and design) is astonishing without being pretentious.

No reservations were needed for what turned out to be our best lunch in the UK, straight off the boardwalk in Lyme Regis, where we dropped into a seaside table after many hours spent exploring the tiny village and hillside hidden bench gardens of Beer, in Devon, on the Jurassic coast. Here we found exquisite local oysters and cod - you can see the fishing boats coming in if you get out there early- and enjoyed an easy camaraderie with the staff that extended to everyone soaking in the sun on the patio. It’s such a joy when find an establishment that, like Barndiva’s, depends equally upon tourism and local patronage, knows how to make everyone feel welcome. The food was fresh and delicious. An elderly woman said hello as she was wheeled to a corner table where it was clear she always dined. An Indian family with young children shared their bottle of wine with the table next to them, and then with us. The weather was sublime. There was a small but wonderful moment when I noticed everyone dining was slyly keeping an eye on the little ones running back and forth across the promenade that led to the sea. We would never see any of those people again. It didn’t matter.

Images above: floral delivery to our hotel in BA at the wonderful Jardin Escondido ; Buenos Ares food images, El Preferido de Palermo ; Mercado de San Telmo; our lovely bartender @CoChinChina.Bar.